Dr Joanna Kirman talks about how a virus replicates. In the replication process, it can mutate producing different strains of the virus. Some viruses (such as rotavirus or the flu) can mix and match their genetic material to produce very different strains from the original strain. H1N1 (swine flu) is an example of this.

Transcript

DR JOANNA KIRMAN

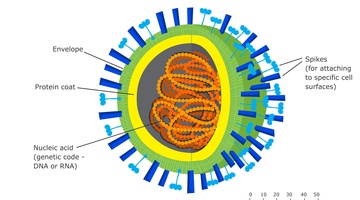

A virus is a very, very simple thing. It’s not a living organism because it cannot replicate by itself. It needs to invade a host cell and basically hijack that host cell and take over that host cell in order to replicate. It’s just a coat of protein that covers up some nucleic acid or some genes.

So it can’t do very much, but once it infects a cell, it takes over that cell so that cell now can no longer do its usual function. And its job is just to make more of itself so it will just replicate and replicate thousands of times within that cell. A single virus can infect a cell and make, you know, tens of thousands of copies of itself within that cell in just hours.

Some of the ways that the virus replicates are a bit sloppy. With our own cells, we’ve got a lot of kind of proofreading enzymes that can come along and make sure that, when you’ve made a new cell, that it’s actually copied the gene sequence perfectly. But the virus doesn’t actually want to have that because it wants the ability to be able to mutate.

So when it’s made 50 000 new copies of itself, they are not all going to be 100% perfect. So it’s like you’ve written down the alphabet, but instead of writing a J, you’ve added an extra N or something like that. So it will just occasionally make a mistake that means the immune system can no longer recognise it, and then that one will be the one that survives, goes and infects a new cell and makes another 50 000 copies of itself, and before you know, you’ve got a new strain emerging.

And it does depend on the type of virus as to how quickly mutations will occur. Some viruses, like flu or rotavirus, for example, actually have their genes, rather than in one long piece, chopped up into little pieces. Say I caught a strain from one person and a strain from another person at the same time and they infect the same cell, they can actually jumble up and mix and match their little pieces of genetic material and create a very, very dramatic mutation as a result of having large chunks of their genes from a whole different virus.

And that is what actually creates flu pandemics, for example. If we actually look at the gene sequence of the current circulating swine flu, it’s a mix and match of swine flu, bird flu and human flu. It has actually got genes from three different types of flu that have jumbled up together. It is actually infecting a lot of younger people who haven’t seen that virus before because our immune systems have never encountered it before. We have got no immunological memory to it, and so we are quite vulnerable to it.

Acknowledgement:

C S Goldsmith and A Balish, CDC Centres for Disease Control & Prevention